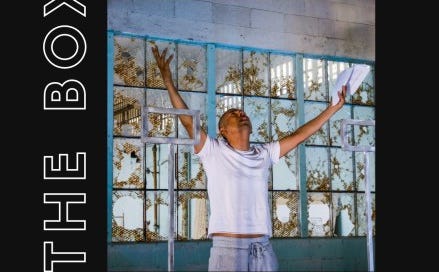

“The BOX” Virtual Performance: A Play About Solitary Confinement by Sarah Shourd

Performances October 1st and 3rd

ON SEPTEMBER 28, 2020 BY JUSTICEARTSCOALITION IN ART FOR JUSTICE, BLOG

by Isa Berliner, JAC Intern

On October 1st and 3rd, audiences from around the globe are invited to a live Zoom performance of The BOX, a play about solitary confinement. Written by a survivor, Sarah Shourd, in collaboration with other survivors, The BOX is a story of human connection and resilience — a piece of transformational theater that asks us to re-examine long-held notions of punishment as it reveals the tragic, and sometimes painfully comic and absurd, realities that dictate life “inside the box.”

This unique Zoom production comes at a moment when millions of people around the world have new reason to resonate with the message of isolation. While Shourd certainly didn’t write The BOX to be performed during a global pandemic, she explains how “the experience — of being separated from loved ones, of being quarantined, of living through a crisis of epic proportions with no clear end in sight— can be a window into the ongoing suffering, deprivation, and resilience of our incarcerated population.” These stories demonstrate the fortitude that has kept these men and women alive, and offer insights into the perseverance we need as individuals and as a society to get through this pandemic and whatever we face next.

Despite the remarkable parallels between The BOX and our current global moment, the story behind this play actually begins over a decade ago. In 2009, Shourd was working in Syria as a journalist and ESL teacher when she was captured by Iranian border police while hiking around a popular tourist destination in Iraqi Kurdistan. She was tortured and imprisoned as a political hostage, spending 410 days in incommunicado solitary confinement — a form of detention considered cruel and unusual punishment under international law.

Upon her release and return to the United States, Shourd was shocked and horrified to discover that tens of thousands of people in the U.S. are held in similar conditions to what she experienced in Iran but for much longer — years or even decades. She began writing and advocating against the overuse of solitary confinement in U.S. prisons, investigating and uncovering stories from the “deep end of the prison system.”

“I had a need to tell the story in a more intimate, personal, way,” Shourd recalls. Journalism and theater had always been inter-connected in her work: in her 20s, she used theater to demonstrate against the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and to tell the stories of Zapatista indigenous communities in Southern Mexico. Empowered by her experience, she turned to political theater.

The question on Shourd’s mind was how to reach people who may not see the humans behind the statistics: “someone that may not be persuaded by the data, that may not be persuaded by the scientific studies or the facts, or may not be able to make something real and tangible and human out of the number.” While the numbers themselves are staggering — of people we incarcerate in this country, of people in solitary confinement, of how long people are kept in these conditions — Shourd points out that such disturbing statistics can have the unintended consequence of depersonalizing the issue. “How can you wrap your head around 80 to 100 thousand people in isolation a day? You really need to focus on a few of those people to understand their stories and get to know them as human beings.” And so, the idea for The BOX was formed.

Shourd spent the next three years conducting an in-depth investigation into solitary confinement in the United States, interviewing 75 prisoners in 13 prisons across the country. She explains that while the suicide rates in solitary confinement are much higher than the rest of the general prison population, many people “still choose life.” Shourd was struck by the kindness and resilient humanity of the people she met: the way they could make her laugh and would make the most of every human interaction. Informed by her personal experience and the people she got to know, The BOX was born.

“The BOX is about how humans will find a way to connect with each other, regardless of the obstacles and the barriers between them. The more governments or carceral systems try to separate us, the more hungry we are to find each other.”

In 2016, The BOX premiered at San Francisco’s Z Space Theatre to sold out audiences of over 3,000 people. The show went on to be performed in a historic production at Alcatraz Islandin 2019, and has been adapted into a graphic novel called Flying Kites. Shourd is always writing and rewriting and adapting the play, breathing new life into the story. Now, with this Zoom production, Shourd is working with what she views, in many ways, as an entirely new piece of art. “Storytelling is always taking advantage of new mediums, and I think that Zoom as a medium is still in its really early stages when it comes to entertainment… I think we’re on the eve of a new way of engaging with live theater virtually.”

Stepping into the role of director, Shourd describes how she and the cast have tried to approach the work with no preconceived notions. They are drawing from the experience of the previous productions, but with “a beginner’s mind,” responding to the current moment. For Shourd, being able to draw on the parallels to people’s “shrinking world” during the COVID pandemic is one of the most powerful things about this performance: “we’re all suffering that isolation and can relate to the subject matter in a new way.” Shourd reflects that there’s a rawness with a Zoom production: this performance is streaming live into the audience’s homes, directly from the actors’ homes.

While working with Zoom has been wonderful and expansive in some ways, Shourd has found it limiting and frustrating in others. There are aspects of the production that have proven to be easier through the virtual platform, such as how the consistency of what audiences will see allows Shourd and her technical designer to more specifically craft what is in every viewer’s frame. But at the same time, Shourd laments that there’s, “an intimacy and a visceral quality that’s lost over Zoom… It can be quite alienating.”

The medium of Zoom, by nature, puts everyone into disconnected boxes — reducing each person to a disembodied face. “There’s not a lot of depth to Zoom, so the physicality is lost and Zoom theater becomes a lot about face and hands and voice.” Nevertheless, the loss of intimacy makes this virtual production all the more impactful. In this way, Shourd remarks, “the message of the play is kind of baked into the platform itself,” emphasizing the dehumanization of reducing someone to a pair of eyes or a food slot.

The costumes and props have been shipped to the actors, and the cast is rehearsing virtually. A large part of using Zoom, Shourd explains, is finding creative and interesting ways to use props and taking advantage of the camera’s ability to create illusions. One of the most difficult elements of the show in traditional live theater is showing how prisoners pass notes to each other, through what is known as “kite flying” or “fishing.” Using a line made from elastic in their shorts or a torn piece of sheet, prisoners in solitary confinement across the country learn to very adeptly sail notes to each other underneath their doors. In live theater, actors struggle to learn and accurately portray this practiced art, but through Zoom, they’ve been able to embrace the platform’s potential for smoke and mirrors and craft a consistent method.

The “kite flying” is essential to conveying one of the largest themes in the play: how do these prisoners find themselves and find human connection against all odds? Shourd states, “It’s a play about resistance – about how these prisoners find each other and get to the point where they were ready to risk their lives to participate in a collective resistance against the conditions they’re in.”

The BOX can be meaningful for those who have survived solitary confinement, as well as their families and loved ones.

“Art and theater is absolutely necessary as a form of witness, and for the healing and restoration of dignity to communities of people who have been deeply wounded by this practice. I think that art is like a fire or a hearth around which communities can join or gather and reignite their spiritual connection and heal.”

Shourd also hopes The BOX can reach an audience of people who have never been to prison and are not at risk of going to prison. It’s these communities of privilege that really need stories, “to help them mine their own experiences of isolation and hopefully deepen their empathy for and outrage against what we’re doing in our prisons.” Shourd hopes that youth in particular can connect their experiences of separation and disconnection to our senseless and cruel “justice” system — to see that it doesn’t rehabilitate people and it doesn’t make our society any safer — and be called into prison reform and prison abolition.

Shourd invites anyone who is feeling alone during the pandemic to join this global audience. Unlike anything theater-goers have seen before, the three virtual performances are sure to be powerful and moving. There is no admission cost, but registration is required to attend. Additionally, the Pulitzer Center is hosting a webinar discussion the week after the performances with Shourd and Damien Brown, one of the actors who is also formerly incarcerated: “we want the conversation to keep going.”

Come see this incredible story of human resilience in the face of dehumanization and isolation: October 1st at 4pm PST and October 3rd at 11am and 4pm PST.

“We can do so much better, and we deserve better. I really hope that this is a moment of reckoning and awakening.”

Sarah Shourd is an award-winning author, investigative journalist and playwright based in Oakland, CA. Over the last decade the majority of her work has centered around exposing the inhumanity of solitary confinement and the ways it which the practice enables mass incarceration in U.S. prisons. Shourd’s approach to her work in many ways reflects her unique life experiences. After the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001, she became actively involved in the antiwar movement while finishing her undergraduate work at University of California, Berkeley. During this time, Shourd also lived as an International Human Rights Observer in Zapatista indigenous communities in Chiapas, Mexico. In 2008, she moved to Damascus, Syria to study Arabic, teach Iraqi refugees, and start out as a journalist. In 2009, Shourd’s life took a dramatic turn when she was captured by Iranian border guards while hiking near a tourist site in Northern Iraqi Kurdistan and imprisoned as a political hostage. Shourd was tortured and imprisoned in incommunicado, solitary confinement for 410 days in Iran’s Evin Prison.

After her release in 2010, Shourd became an internationally known advocate against the overuse of solitary confinement in U.S. prisons. As a UC Berkeley Visiting Scholar, she conducted a 3-year investigation into isolation in U.S prisons, interviewing 75 prisoners in 13 prisons across the U.S. Based on this investigation, Shourd wrote and produced a play, The BOX, which premiered in San Francisco in 2016 to sold-out audiences. She also co-authored an anthology, Hell is a Very Small Place, comprised of the stories of incarcerated Americans she collected. Her Op-eds and journalism have been published by The New York Times, Mother Jones, The Daily Beast, CNN, San Francisco Magazine, San Francisco Chronicle, Reuters and many more. In 2015 she was a Ragdale Artist-in-Residence, one of 7×7 Magazine’s HOT 20 in 2016, a recipient of the GLIDE Memorial Church Community Hero Award in 2016 and in 2018 she was chosen for the prestigious John S. Knight Fellowship at Stanford University.